In recent years an increasing number of cardiovascular outcome trials have been completed in patients with diabetes and obesity with high cardiovascular risk.

In one of these studies, Worldwide Clinical Trials supported the development of a lifestyle modification program in partnership with the sponsor. Designed to encourage diet and exercise, this program included a survey of study participants to evaluate its impact. The survey results revealed that engagement in the program was lower than anticipated. However, there are several lessons learned that can be applied to similar healthy lifestyle initiatives in cardiovascular outcome trials.

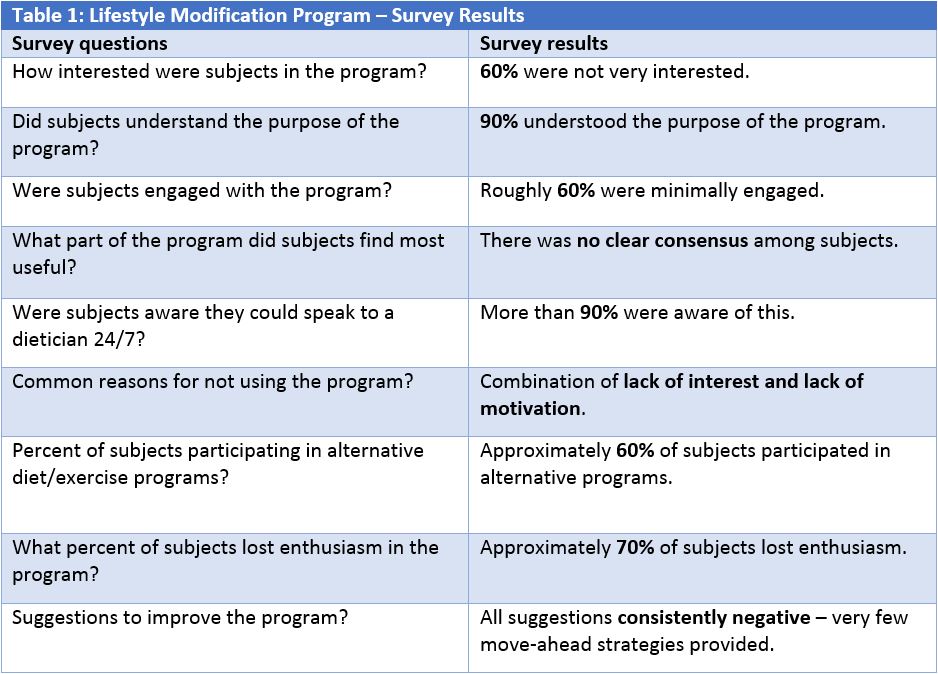

To illustrate the challenge, 60% of survey participants said they were not very interested in lifestyle modification. Although most subjects understood the purpose of a diet and exercise program, they generally had minimal engagement, low motivation to follow the program’s recommendations, and little to say about how the program could be improved.

Table 1 (below) shows a sample of the survey responses collected during the cardiovascular outcome trial.

Webinar provides more details about our expertise in cardiovascular outcome trials

These responses say volumes about the challenge of adding lifestyle modification programs to large cardiovascular outcome studies. We’ve detailed our lessons learned here to support the next generation of these programs designed for diabetes and obesity clinical trials. To hear more about our experiences in this area, please visit the Worldwide webinar recording, “Eavesdropping on the Experts: Five Emerging Trends in Cardiovascular Research.”

Based on our experience in cardiovascular outcome trials, here are a few tips to improve lifestyle modification programs:

1. Think big when developing lifestyle modification programs for a cardiovascular outcome study.

When first developing the lifestyle modification program it makes sense to approach the task with an open mind because at this stage “the sky is the limit.”

Take a close look at the variety of lifestyle interventions that could work over the long term for diverse populations that have many patients suffering from comorbidities, such as Type 2 diabetes and obesity. These potential modalities include:

- • Customized recipes and physical activities programs,

- • Ability to participate in a weight loss program,

- • Access to a website with healthy lifestyle materials,

- • Direct dietician contact with unlimited one-on-one consultations about diet and exercise, and

- • Text message reminders and scheduling tools.

2. Consider recipe books as a tangible part of the cardiovascular outcome study.

One bright spot in the lifestyle modification program was a paper recipe booklet with customized recipes translated into local languages. It turned out to be the most effective tool among the many options we provided for the clinical study participants. They really seemed to like having something tangible to carry away from their site visits.

This was a traditional recipe book translated into local languages and modified regionally because the way a certain dish is presented in Poland, for example, is different from how it is served in Mexico. The modifications were numerous because the cardiovascular outcome trial included a diverse geography, as is usually the case in these outcomes studies. To produce the book, we interacted on all levels with clinical sites, patients, and health authorities, managing feedback from some regulators who went so far as to recommend a particular ingredient before approval.

Unfortunately, it was not always easy for study participants to get the recommended healthy fruits and vegetables. In regions where these foods are not readily available, participants saw it as a chore to travel to obtain these items. People facing this challenge often fell back into old habits of unhealthy eating.

3. Approach technology investments for a cardiovascular outcome study with caution.

Although patients responded favorably to the recipe books, they were less excited about the technology assets we developed. These technologies included an advanced website that offered motivational and healthy lifestyle materials, text-message reminders about exercise and appointment follow-ups, activity trackers, and apps for documenting meals.

Age may have been a factor in the lack of interest in technology since the median age of respondents was 65. While many of us know web savvy grandparents, few participants in this clinical study got excited about the digital options. This was the case across all geographies.

Even in the U.S. there were barriers to implementing technology. For instance, we used tablet computers to support the clinical sites but data collection was inconsistent. The tablets were nice, but most site personnel said they would have rather received another tool. In fact, some staff refused to use the tablets. Other site personnel liked the concept but struggled to make it work. A few study coordinators with no wireless access due to firewalls and other security restrictions said they had to visit nearby restaurants to get online and sync data.

4. Enable participants in a cardiovascular outcome study to discuss lifestyle modification with physicians and nurses.

When we were designing the cardiovascular outcome study, many patients said they would like the option of speaking with a registered dietician. This option was subsequently provided, complete with dieticians who spoke the local language and provided specific counseling. If a patient had a certain comorbidity, for instance, the advice would differ from that given to another individual. This option to speak with a dietician was added to the healthy living programs that many clinical sites already had in place.

As noted in the table above, 90% of the participants were aware they could meet privately with a dietician. Unfortunately, very few people took advantage of this access. Improving their diet may have sounded like a good idea initially, but discussing it with a professional proved to be a barrier.

On the other hand, personal interactions with physicians or nurses at the clinical sites were something participants liked and wanted to do more.

During study design, we also considered providing vouchers for exercise programs or membership to Weight Watchers or similar groups. However, since not all participants globally would have access to these options, we provided participants with our own messages of encouragement to modify diets and increase exercise while participating. The survey found a muted response to this supportive messaging, with only about 60% of subjects participating in alternative diet or exercise programs.

5. Continue healthy lifestyles research to improve future cardiovascular outcome studies.

To understand this limited uptake and why 70% of participants lost their enthusiasm for the healthy lifestyle tools, we asked how the lifestyle modification program could be improved to help them stay motivated and stick with the program. However, there was no consensus among respondents.

With no clear guidance from participants and a growing need for engagement in healthy lifestyle programs, we recommend continued research to improve the future of cardiovascular outcome trials.

To learn more about Worldwide Clinical Trials’ expertise in cardiovascular clinical trials, read about our phase I-IV experience spanning varied vascular disorders, heart disease, and cardiometabolic indications.