In past blogs, we have discussed the necessity for improving screen failure and recruitment rates in Alzheimer’s disease research. To reduce this failure, Worldwide Clinical Trials takes an uncommonly proactive 4-step approach to increase the predictability of patient screening. Developed by Worldwide’s experts, who have 40 years of Alzheimer’s research experience, this unique strategy begins during clinical trial protocol development, involves activities prior to both patient consent and randomization, and centralizes eligibility review to improve enrollment speed and outcomes.

Here is an outline of the Worldwide strategy to improve Alzheimer’s disease research in clinical trials:

- Ensure clinical trial protocol will result in minimal patient burden.

- Understand which patients are more likely to qualify before formal screening begins.

- Positively influence semi-predictable reasons for screen failure.

- Introduce a centralized eligibility review system to improve enrollment decisions.

Here, in the first of two blogs on the Worldwide approach, Talking Trials reviews two cases of high profile screen failure in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease research, as well as general causes of failure. In part two of the series, we’ll take a deeper look at Worldwide’s uncommon strategy for reducing this failure. Many thanks to Worldwide’s Vice President of Neuroscience Tom Babic, MD, PhD, who provided the information for this series during a Worldwide webinar on Alzheimer’s disease research (1).

Early-stage Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials had twice the typical screen failure rates

In recent years, screen failure has been especially daunting in early-stage or “prodromal” Alzheimer’s disease research. Note that prodromal patients are considered to be those who experience deteriorating memory but remain functionally independent. Early disease is also defined as mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. The two cases of high profile failure discussed here occurred in prodromal Alzheimer’s clinical trials that experienced screen fail rates of 80% and 76%, more than twice the typical failure rates of 25% to 30%.

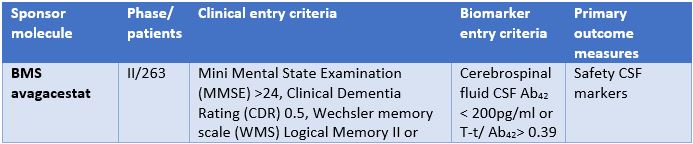

Table 1 summarizes the two high profile screen failures in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease research (2).

In the avagacestat phase II clinical study outlined in Table 1:

- 1,350 patients were screened.

- 270 patients were randomized.

- 80% screen failure rate was seen.

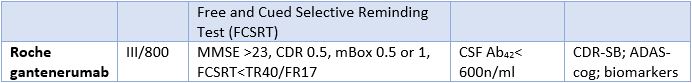

The gantenerumab phase III clinical trial had a similar negative outcome:

- 3,000 patients were screened.

- 710 patients were randomized.

- 76% screen failure rate was seen.

A significant and increasing amount of evidence suggests that high study failure rates in Alzheimer’s clinical trials and other central nervous system clinical trials are partly attributable to inappropriate patient selection (3). The difficulty of patient selection can be more pronounced in early-stage studies.

Focus on early-stage Alzheimer’s disease research increases need to reduce high screen failure

With growing demand for clinical research in the earlier stages of Alzheimer’s disease, there is increased urgency to reduce high screen failure rates and successfully complete studies in order to develop disease-modifying therapies. See Figure 1 for the common causes of screen failure in Alzheimer’s clinical trials.

Causes of Screen Failure (percentage of total)

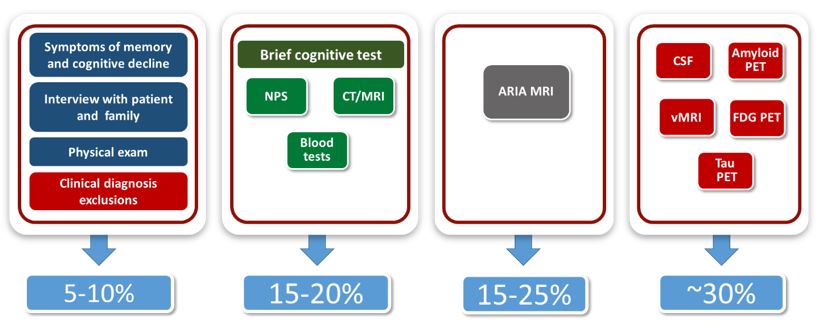

Figure 1: The causes of screen failure in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials and percentages of failures by segment of screening test.

Moving from left to right in Figure 1, the tests are segmented from least to most expensive and from easiest to most difficult to conduct. The most common screen failures in Alzheimer’s disease research are due to the following:

- 5%-10% of screen failures happen during the assessment of symptoms of memory and cognitive decline, interviews with patients and their families, physical exams and clinical diagnosis exclusions.

- 15%-20% of failures occur as a result of brief cognitive tests, neuropsychological investigation, routine computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and blood tests.

- 15% to 25% of screen failures result when study volunteers do not meet the criteria of the amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) MRI.

- Finally, ~30% of screen failures follow highly sophisticated lab tests, including those using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), plus tests that employ Amyloid positron emissions tomography (PET), volumetric MRI (vMRI), fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET, and Tau PET.

Because overt clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease are not evident until considerable change has occurred within the brain, clinical trials in the early stages of the disease are especially difficult (4). As Alzheimer’s disease research moves to treating patients earlier in the disease continuum, there is increased urgency to reduce screen failure in order to improve patient recruiting.

Thanks for your time in reading part one of this series. In part two, we will go into more detail about Worldwide’s uncommonly proactive 4-step strategy to reduce screen failure in Alzheimer’s disease research.

References

- Zucker J, Babic T, Zupancic B. “Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trials: Improving Screen Failure and Recruitment Rates.” Worldwide Clinical Trials webinar, November 10, 2016.

- Schneider LS, et al. “Clinical Trials and Late-Stage Drug Development for Alzheimer’s Disease: An Appraisal from 1984 to 2014.” Journal of Internal Medicine (March 8, 2014): .

- Sacks LV, Shamsuddin HH, Yasinskaya YI, et al. “Scientific and Regulatory Reasons for Delay and Denial of Initial Applications for New Drugs, 2000-2012.” JAMA, 311(4) (2014): 378-384.

- Cummings J, et al. “Drug Development in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Path to 2025.” Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy (2016): 8:39.