By: Kerri Padgett, Courageous Parents Network

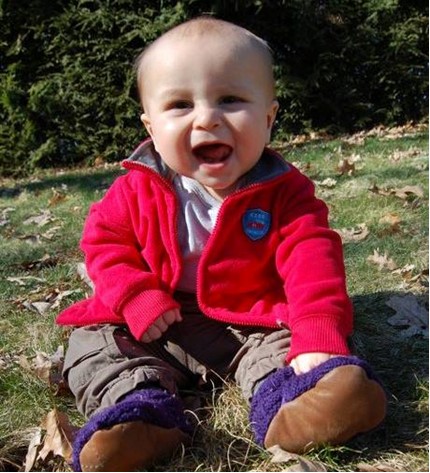

This year, I will celebrate the life of my son, Kai, for the 10th time since his passing from hypothalamic optic glioma at the age of two.

I feel immense gratitude for the support we received during his cancer journey, but there are also moments when I wish I’d had more support. I know there are many families out there needing more, too. I am sharing our story during Brain Cancer Awareness month to offer opportunities to consider an improved experience for families facing one of the hardest things life can bring.

Kai received a formal brain tumor diagnosis at eight months of age, after I spent months working to convince doctors that he was regressing at a concerning rate and something was wrong. During this time, we saw over a dozen pediatricians, neurologists, and ophthalmologists trained to find the most probable cause of his symptoms. This practice makes sense in theory, but for Kai, this meant our journey to diagnosis was long, as the “most likely answer” never quite fit. The diagnosis was equal parts devastation and relief – relief after months of trying to figure out what was wrong, and devastation to know Kai had cancer. But, it was the first step towards helping my baby feel better.

Though I faced many obstacles and hurdles to getting my son seen and his symptoms to be taken seriously, I had many advantages that many other people may not. As a native English speaker, I had the language needed to interact with his doctors, to convey his symptoms, and to converse about possibilities. I had the health insurance, income, and job flexibility to do what it took to find answers.

But this is not the story of many Americans or people across this world. Access was an advantage I had, and my heart breaks to consider the experience of parents going through the same situation as us, without it.

Navigating The Confusing Feelings Of Diagnosis

When Kai’s diagnosis was explained to me, I was told that as far as brain tumors go, we were lucky to have a “good tumor.” We were told that he was expected to be a “long term survivor,” with an 80% chance of survival. And yet, I could not help but think about the other 20%. It was an isolating time. My friends and family felt I was being too negative and encouraged me to find hope.

I understand now that what I was going through is called anticipatory grief — an extremely common experience for loved ones and patients facing the possibility of death. Anticipatory grief is grieving over the potential for loss, even though it may not happen soon or at all. Knowing what I know now, I wish I had received support at that time from the hospital. I was lost in my head thinking about how he may never get his driver’s license, attend his high school prom, or even graduate from kindergarten. Kai was just a baby, with so much life he deserved to experience.

At the end of Kai’s care, I came to lean on the palliative care teams at our hospital, but there are many touch points along our story where I did not have this help, and the burdens I carried as a parent of a sick baby were heavy. Palliative care teams offer support at any stage of illness, to assist with comfort and management of physical and mental impacts of disease. At the time of his diagnosis, I was not offered this care and did not know it existed. When I was experiencing the isolation of anticipatory grief, I wish I’d had this support.

Kai began chemo shortly after his diagnosis. We were lucky enough to live semi-close to the hospital where he received treatment. Weekly, I drove into Boston’s Children’s Neurology, a journey that took up to two hours one way. Each week he would receive hours of infusions of chemo that would make him sicker than when we arrived that day, in the hope it would save him in the end. All too often, I would take the highway home after the appointment with a baby vomiting in the backseat from the chemo filling his little body. I couldn’t reach him immediately, and the fear he would aspirate or choke was nearly paralyzing. On some treatment days, my mother was able to come with us — an unbelievable relief to me, but again, a privilege many families do not have.

Considering Clinical Trials

When it became clear that Kai’s chemo plan was not helping, we turned to clinical trials. The oncologist presented three trials to me, explaining the potential benefits and downsides of each. Going home from the clinic that day with three packets in hand, it felt unbelievable that this decision was mine. What if I chose the wrong one? What if I mess up the medicine at home? What if it doesn’t work and he dies? I was made to feel lucky to have options of trials to choose from, but it also felt like playing Russian Roulette with my child’s life. How could I, his mother, not a scientist or an oncologist, be making this decision?

Any parent having to sign a protocol that includes a potential side effect of heart attack, secondary cancer or DEATH, should have access to the support of a palliative care specialist. Honestly, I had been contemplating the possibility of Kai’s death since diagnosis. No matter how hopeful the statistics or how positive we remain, most parents are in fact thinking about this possibility from day one. We feel guilty and wrong for thinking these things, but how could we not?

Kai, “failed” off the second protocol in a few short months. I again questioned if we were doing the right thing. I asked our team what happens if we don’t want to do any more treatment? When will I know when enough is enough? They assured me we were “not there yet.” There were more treatments to try, and the Ethics Board would have to get involved if I wanted to stop treatment.

I knew I was not ready to stop treatment, but I also knew that I did not want him to suffer. At that time, I had no idea the potential implications of the ethics committee. In fact, I quite liked the idea of having more people to talk this out with. This was another time I wish I had palliative care support – they are trained in considerations for continuing or halting treatment and can support families with this excruciating decision.

Making The Impossible Decision

The third protocol made him sicker than he had ever been. We had many difficult days and nights in those last few months, and I knew in my heart that this was it. It was clear to me that he was suffering.

Palliative care was finally introduced at this time. I could share with them my deepest fears and worries and talk through our options in a way that felt collaborative and informed yet also focused on our family’s goals and priorities for Kai. I knew we needed to stop treatment, and this time, the team agreed.

Kai lived three more months at home, away from the hospital. As the chemo left his body and he began to feel better, we had some of our best days. He began feeling and looking so much better, and I began questioning my decision. I started looking at trials that he might qualify for – it is hard to not be lured by the glimmer of hope a clinical trial offers. It can easily blind you from the reality that is in front of you, especially when that reality is staring in the face of death.

In his last few weeks, I also needed to make sense of it all, make his suffering in his short life mean something, and I was unbelievably grateful to find out I could donate his tumor to research. Because of his chemo, his organs could not be donated, but his tumor could be used to advance the understanding of his cancer. I am so grateful I was told of this opportunity before it was too late. For the families I interact with going through similar experiences, too often I hear they found out too late, or never at all.

Kai died peacefully, just after his second birthday. Sixteen months of treatment and three protocols later, we became the 20%. For a long time after Kai’s death, I struggled with the concept of hope, especially in terms of cancer treatments and clinical trials. Clinical trials give hope where there once was none, BUT the outcomes are not guaranteed. I wish it remained more front and center in my mind that trials are truly experimental. These were not approved treatments with proven evidence of helping patients. These treatments were unknown, but this often was lost in discussion as I was forced to make impossible choices.

We owe it to patients and families to show up for the whole conversation. We can offer much needed support at more touchpoints in their journey and continue to strive for a better patient experience as we work to find better treatments for children like Kai.

Kerri is part of the Courageous Parents Network, an organization that “empowers, supports, and equips families and providers caring for children with serious illness.” They work to empower families and parents to believe in their ability as caregivers, offer support for their healing journey, and connect them to pediatric palliative care. To learn more about palliative care, resources for parents, and the work the Courageous Parents Network is doing, click here.